[

Prime Minister Mark Carney is meeting Inuit leaders Thursday in Inuvik, N.W.T., as he ramps up his outreach to Indigenous communities about his plan to fast-track major nation-building projects.

Carney arrived on Wednesday, attending a community gathering before meeting with Inuit leadership from across northern Canada.

Inuvik, one of Canada’s northernmost towns, is hosting the prime minister, several cabinet ministers and Inuit leaders for what’s known as the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee on Thursday.

Carney and Natan Obed, the president of the national Inuit organization, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, are co-chairing the meeting, which is expected to have a heavy focus on the Liberal government’s major projects law.

The law, known as C-5, enables the federal cabinet to invoke emergency-like powers to deem projects, such as pipelines, railways and transmission lines, in the national interest and to approve them upfront.

That approval comes even before an environmental assessment and the Crown’s constitutional duty to consult affected Indigenous communities is complete.

Carney held a similar summit in Gatineau, Que., with First Nations chiefs earlier this month. Some said they supported his efforts, while others stormed out — calling it political theatre. First Nations in Ontario have launched a court challenge to C-5 and a similar provincial law.

Carney hasn’t received a ringing endorsement from Inuit leaders for his “build baby build” agenda, but so far the reception has not been as confrontational as the meeting with First Nations.

“I’m looking forward to hearing from the prime minister himself regarding how he intends to work with us,” said Duane Ningaqsiq Smith, CEO of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, which represents six Inuit communities in the western Arctic, including Inuvik.

Northern politicians and Inuit leaders have been pitching Inuit-backed projects, hoping they will be among those deemed to be in the national interest.

One such project is the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link, with the goal of connecting Nunavut’s mainland communities to Manitoba’s power grid and joining the rest of the country in enjoying high-speed fibre-optic internet.

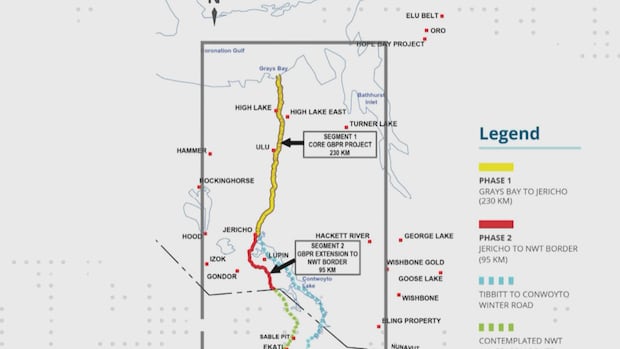

Another, the Grays Bay port and road, could offer Nunavut easier access to its resource-rich areas and western provinces a direct link to the Northwest Passage.

The Grays Bay port and road would connect ice roads in Yellowknife, through Nunavut, all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Some are saying the impacts of the project are too great to ignore. The CBC’s Emma Tranter reports.

A subsidiary of the region’s Kitikmeot Inuit Association is proposing to build a deepwater port on Nunavut’s mainland in the Coronation Gulf.

“It’s kind of a win-win situation for everybody,” said Fred Pedersen, the executive director of the Kitikmeot Inuit Association. He said taxes and royalties earned from the economic development made possible by the port and road would cover the cost in a matter of years.

“It has so much potential for critical minerals. It will open up, but also it will assert our sovereignty in the Arctic,” said Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok.

The project is currently undergoing the territorial environmental review process, but already has the backing of Akeeagok and N.W.T. Premier R.J. Simpson.

N.W.T. also wants a road down the Mackenzie Valley, which Simpson sees as a critical defence link.

The former executive director of the NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines, Tom Hoefer, notes that much of what the North considers a project in the national interest is basic infrastructure that most communities in the rest of the country already have.

“They’ve been underinvested in by Canada over the last 50 years,” Hoefer, who was born and raised in the North, told CBC News in an interview. “And so we’ve sort of been asleep at the switch on that front.”

Hoefer and others argue that such projects would have the potential to unlock significant investment and economic growth in the North and nationally.

Smith, of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, told CBC News he will be raising these gaps with the prime minister at Thursday’s meeting, admitting that while they might not be what many consider nation-building infrastructure, they are critical his people.

Inuvik trucks propane about 2,000 kilometres from B.C. and up the gravel-packed Dempster Highway, at tremendous cost, especially when, Smith and others point out, the region sits on substantial natural gas reserves.

The Inuvialuit Regional Corporation is attempting to develop a well outside Inuvik to provide a domestic solution to what Smith calls concerns over energy security.

At the same time, Inuvialuit leaders say concerns over food security, housing and health care must be addressed.

“My region right now doesn’t even have dental services. So people have to get sent close to a thousand kilometres to the nearest dental facility, if not further,” Smith said. “The average Canadian would not accept that.”

For him, advancing nation-building projects and addressing other infrastructure gaps in the North is not a binary argument. Both need to be pursued.

“We’re Indigenous, everything is interconnected,” Smith said. “We’re supportive of potential opportunities for development … so that we’re able to look after ourselves, which will also help us sustain our culture and well-being and our livelihood.”