[

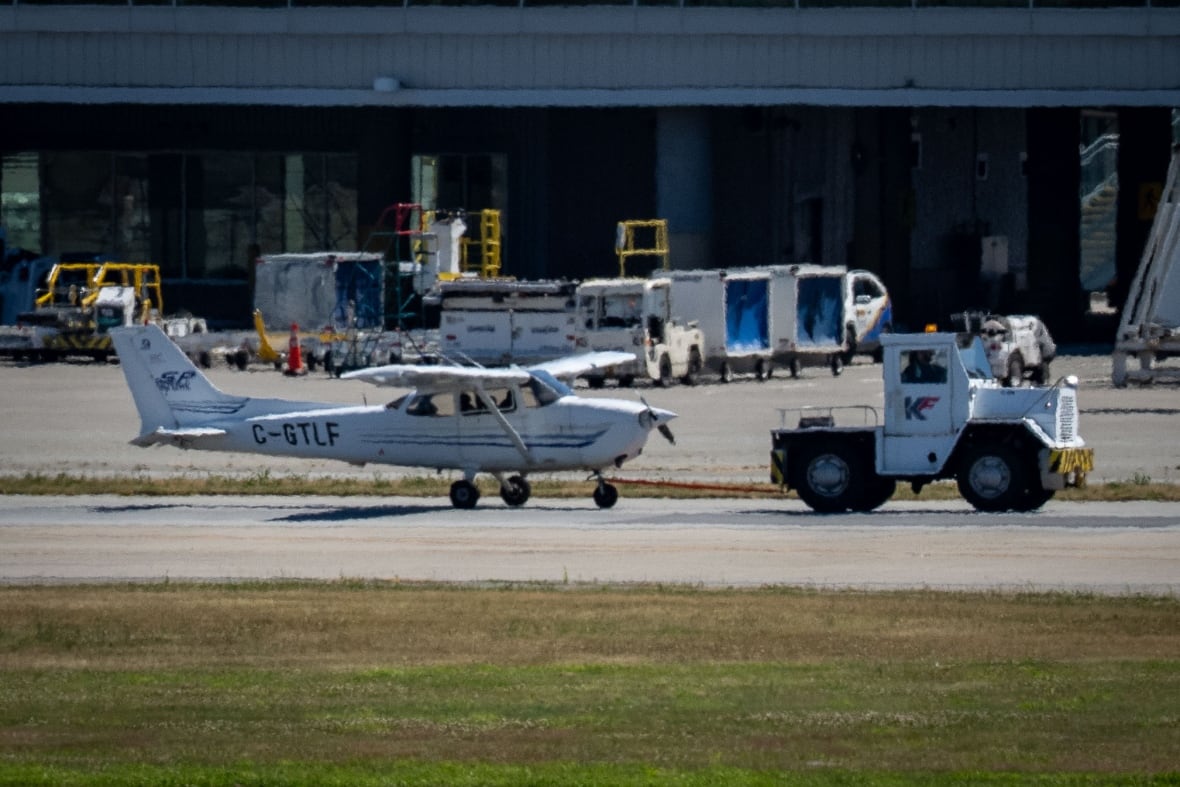

After a scary moment in B.C. on Tuesday, when a man allegedly hijacked a small Cessna 172 plane in Victoria and flew to Vancouver International Airport (YVR) airspace, U.S. fighter jets raced to the scene.

Wait — U.S. fighter jets? Why weren’t they Canadian?

The answer lies in a decision-making process involving multiple defence agencies in Canada and the U.S. as well as the logistics of refuelling airplanes.

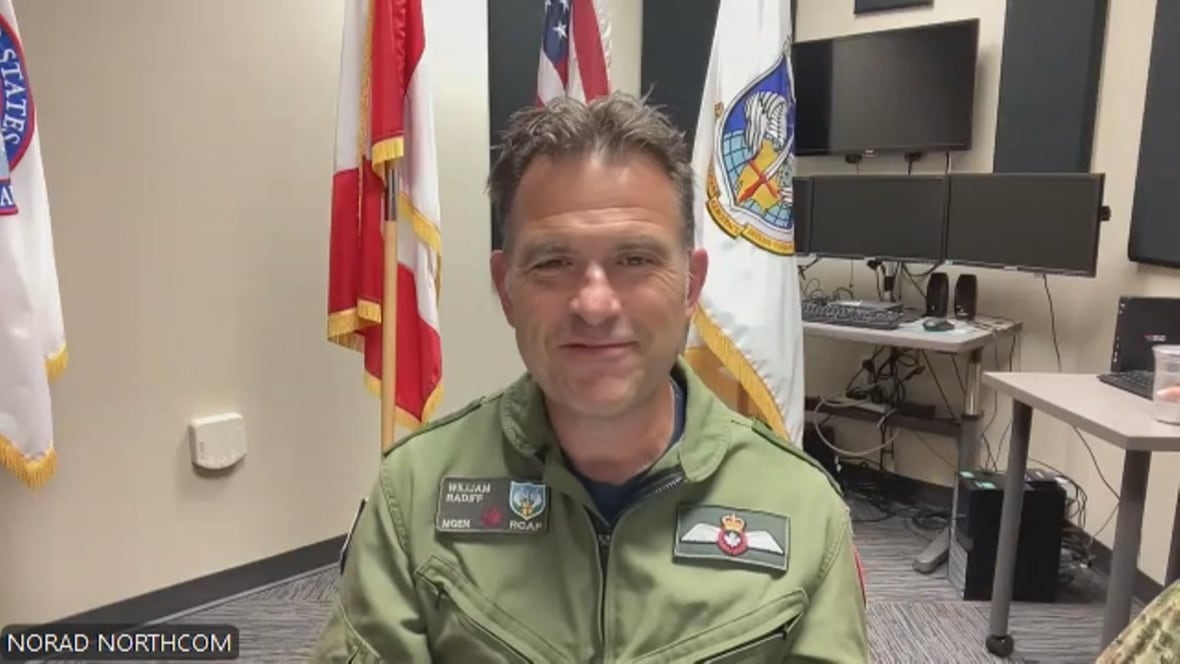

American F-15 fighter jets responded to Tuesday’s incident, but Canadian CF-18 Hornets were quickly mobilized for back up, according to the director of operations of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), Maj.-Gen. William Radiff with the Canadian Air Force.

However the incident at YVR, he said, was resolved before Canada’s Hornets could even take off.

American fighter jets were quick to respond when a small plane was allegedly hijacked and landed at the Vancouver International Airport on Tuesday. But why weren’t Canadian jets sent instead? Liam Britten explains.

The Hornets were also far enough away, in Alberta near the Saskatchewan border, that the planes would need to refuel once they arrived in B.C., Radiff added.

Radiff, whose military call sign is “Fat Daddy,” spoke to CBC from NORAD’s headquarters on the Peterson Space Force Base in Colorado Springs, Colo., to discuss how these high-level defense decisions get made.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How does NORAD generally respond to threats?

We have forces across Canada and the U.S. able to react to both internal and external threats to North America.

We do a mission called Operation Noble Eagle, a conference. Typically, it’s in response to what we would say is an internal threat.

We get all the senior leaders that need to talk on the conference, because what we’re trying to do is to build decision space — so, time — for our senior leaders.

We have a series of tactics, techniques and procedures; we will march down these paths and use the assets that we need to use in order to get ourselves in a position to give decision space to our senior leaders in the chain, up to the prime minister and the president.

What happened in the Cessna incident on Tuesday?

The report of the stolen airplane from NAV Canada came in. Canadian Air Defence Sector (CADS) and the Canadian NORAD Region (CANR) get involved and call a Noble Eagle conference.

We bring in general officers, two-stars or higher, responsible for the Canadian Recommending Authority into the conference.

It’s a dual conference with the American Civilian Aircraft Engagement Authority two-star generals.

The RCMP comes on the line. It gives us an idea of what is going on and what has been said.

We take a look at the distances and times involved, and we assessed that the closest fighters to be able to respond and have the most amount of gas when they got there to be able to spend time, and the closest tanker that would be able to service them, was the F-15 fighters that we sent.

We also went to CANR, which started the process to get the CF-18s from Cold Lake, Alta., in case it’s an enduring mission — we want to make sure that we have back ups.

As it turned out, the thing itself resolved before the Hornets got airborne, which is great.

Post-launch, what are the F-15s doing?

Post-launch, the F-15s are under control, in this case, of the Western Air Defense Sector, because, of course, it’s western U.S, but also as they come to cross the border, they would actually then transfer over to the Canadian Air Defence Sector. They would actually transfer over co-ordination.

We practice this all the time.

So particularly from a command and control aspect, because as you can imagine, American armed fighters going into Canada or Canadian armed fighters going into the United States could be a significant emotional [act]. Well, it’s not because we practice it all the time.

Police say the man accused of hijacking a plane in B.C. on Tuesday had posted religious claims online, reflecting an ideological motive tied to saving the world from climate change.

A lot of the actions that were occurring on this Op Noble Eagle conference were the two-star major generals working with the authorities to go, “OK, if this continues down the path, we’re going to need to get F-15s to cross the line.” So we need to have permission from the U.S. and from Canada for that to happen.

This is really seamless because we practice it so often.

If the F-15s had needed to continue, we had all the authorities ready to go and cross the border – it wasn’t required, as it turned out. We assessed the individual wasn’t really posing a threat because he was flying over the airfield as opposed to Vancouver. Still a threat, but where he was flying gave us the ability to go, OK, we’re in a good position.

Who was at the table? Was the Canadian minister of defence or U.S. secretary of defence personally involved?

I can’t give you those details, but I can tell you the intent of that conference is to gather all of the senior leaders, policing authorities and NORAD officials that we should have.

How close did the F-15s get to Canada? No one seemed to see the F-15s on the Canadian side.

I can’t tell you exactly where they got to, but what I can tell you is it makes sense that they wouldn’t necessarily have seen the F-15s based on where they were. One of our tactics, techniques and procedures, is to actually be in a position so we can do something, but so that we’re not necessarily seen.

In this particular case, based on what we had been observing and reports from NAV Canada and the Vancouver tower, we were in a position where it’s like, hey, we probably don’t want to rush in and stick our nose where we shouldn’t have.

We were in a great tactical position for the time that we had, and we could have moved closer as we wanted to.

Why didn’t the CF-18s in Cold Lake jump into this situation?

We scrambled aircraft at this time, but, one of the big factors for Canadian airplanes, if they were going to rush all the way to Vancouver, when they get there, there’s probably going to be a gas requirement.

Then we have to also factor in the timings with where the gas is going to come from.

You said you practice this procedure all the time. Is this a fairly standard operation?

This is a fairly standard procedure — a stolen airplane is not that standard.

Has anything changed with NORAD’s CF-18 capabilities or has availability declined?

The defense of Canada is the No. 1 mission for the military. We don’t see any decline in response from the CF-18 community, and the CF-18 continues to prioritize NORAD as their No. 1 mission.

In fact, there’s been a number of recent upgrades to the CF-18 that have made incredible leaps in technology that make it an even better platform than it already was.

As the relationship between Canada and the U.S. changes with trade tensions and even annexation talk, what is the reality of the forces working together to keep North America safe?

It’s the only bi-national command in the world; it’s been a strong bi-national command since 1958, and nothing has changed.

We don’t ever talk politics at work. It’s not something that we do, nor does it affect what we do.

I would say that we are as tight, and probably tighter than we’ve ever been. As the world around us gets to be more dangerous, I would say that NORAD is even closer than it’s ever been.

But one last thing — we have the watch. That’s the slogan here for NORAD.

To give you a great example, all of the assessors, we all live on-base in homes that actually have a safe, we call it the skiff. It’s basically a classified room that has all of our systems. The days that you’re on duty, you’re either at work or in your house. Because the timelines are so small for answering the phone, you don’t walk the dog; you don’t do all these other things, and someone covers for you when you’re going between work and home.

That’s how important this mission is to us down here. It’s really important for everybody in Canada to know that at NORAD, we have the watch.